Q&A: Italy to build on subsidy-free solar impetus

Having seen Italy’s first subsidy-free solar PV projects secure financing in 2018, dealflow is expected to ramp up in the coming year. inspiratia speaks with Giuseppe La Loggia, managing director and head of renewable energy at EOS Investment Management, about the prospect of double-digit IRRs in the country.

In Italy, solar PV’s race towards grid parity has set in motion a gold rush, with large-scale project development activity building up in 2018.

“I see this period as very exciting,” says Giuseppe La Loggia, who is leading the London-based EOS Investment Management’s strategy in subsidy-free solar, having previously worked on Italian grid parity solar while at Octopus.

“However, given where we stand regarding construction prices, we are already beyond what could be defined as a transition,” he says, explaining that – with the current levels of prices – returns on investment can reach a very generous double-digit mark.

Interest and market activity in the Italian sector is now being compared to the one the industry experienced in the golden years of 2008-2009, but with a big difference.

“My view is that the floor of investment will not be as aggressive — and probably unsustainable — as it was in the era of the feed-in tariffs,” La Loggia says.

At the moment, there is said to be a scarcity of high-quality permitted projects in the country. According to La Loggia, this could be attributed to the fact that the investment dynamics in the country have changed.

“The majority of investment appetite comes from financial players who have no desire to take development risk,” he explains.

On the plus side, this creates a tremendous opportunity for developers with the financial capability to bring projects to a shovel-ready state and then offer them to capital providers.

“To a certain extent, this will keep the balance right, because it will not create an immediate large number of projects available, and it will keep the trend sustainable for the medium and long-term,” La Loggia adds.

Expanding on the fund’s strategy, La Loggia says that, even though EOS doesn’t invest in the development phase, it has an in-house team supporting developers with know-how.

“We kick in financially after the permit is granted and we invest equity in construction — this, in my opinion, is what gives you a smooth double-digit IRR,” he continues.

“Those who prefer to invest in ready-to-commission projects will need to be prepared to sacrifice a portion of these returns,” he adds.

Merchant vs private PPAs

Drawing on the refinancing Octopus completed last January [2018] for five solar power plants of 64MW capacity in the Lazio region, La Loggia is noticing a shift in how banks view debt financing of subsidy-free projects with merchant elements, while underpinned with private PPAs.

“When we closed the deal and a year later refinanced it, our instinct was to attempt the longest private PPA that existed at the moment,” La Loggia explains.

“However, banks are starting to develop a different perspective, where they view long-term PPAs with lower prices as a lost opportunity.”

He goes on to explain that the difference in pricing between a five-year PPA and a 10-year one is significant, merely because lower prices offset the biggest risks the offtaker usually takes.

“Banks are more keen to preserve the value of the project, so they are pushing for more competitive PPAs — for example five-year ones,” he reveals.

In order to mitigate merchant risks, EOS has adopted a conservative approach, where it seeks an initial five-year or 10-year bilateral PPA, relying for the remaining period on electricity price fluctuation forecasts.

“We also take a step beyond by applying our own discounts on these forecasts,” La Loggia adds, stressing the importance of delivering institutional investors more – and not less – than promised.

Corporate PPAs

It is no secret that, despite the enthusiasm around the take-off of private PPAs activity in the country, the expectation of corporates entering in numbers is not equally promising.

La Loggia attributes this trend to lack of necessary legislation, as the Italian parliament has approved the relevant law, but no official decree has been issued to put the law into force.

“We are in this limbo between the general principles of law being there and nobody knowing how to put them in practice,” he comments.

“I would like to hope that the issue is moving forward, but at the moment I don’t see corporate PPAs coming into play for at least the next 6-12 months,” he says.

He also stresses the need to cultivate the corporate PPA culture among the small and medium-sized enterprises that constitute the backbone of the Italian economy, in order to overcome old-style mindsets.

“They are more focused on getting a good price in the short term, and they will need to understand that sometimes certainty is more important than price,” he adds.

Outlook for 2019

La Loggia assigns a substantially positive outlook to Italian subsidy free, thanks to the increased availability of permitted projects ready to go forward.

“2018 has been a year of preparation and behind-the-scenes in what concerns developing projects,” he says. “But the real year of investment will definitely be 2019,” he states.

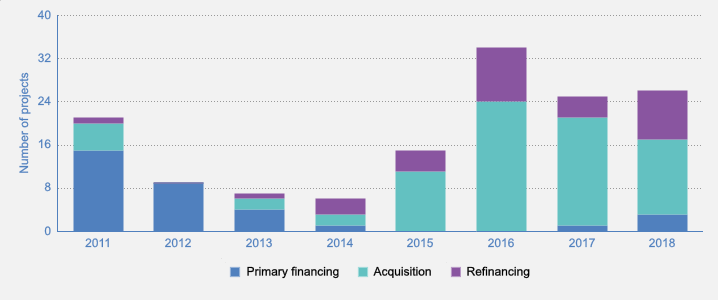

Figure 1. Italy’s closed renewable energy deals, 2011-2018

Source: inspiratia | datalive

He forecasts that 2019 will see investment in approximately 400-500MW of solar projects across the country.

La Loggia foresees investments in the regions of Lazio, Sardinia – although the area has a land limitation in that it prefers solar plants to be deployed only in industrial land – Sicily and Apulia.

“Sicily is starting to really favour projects after a long period of uncertainty and very contradicting views around how and where the regional government wanted solar to be deployed. Even though the permitting process still takes slightly longer than the average, I expect a few hundred megawatts being developed in the coming years,” he says.

According to La Loggia, there is a great potential in the Apulia region, as the area is rich in projects that, abandoned immediately after the end of subsidies, are now being revamped by new investors.

Auctions not enough for 2030 targets

According to La Loggia, the policy tools which the government coalition between the League and the Five Star Movement have proposed are outdated.

“The strategy they are implementing in the upcoming renewables decree has been written with a very old-fashioned mindset still thinking that government subsidies are the only way to grow the sector,” La Loggia says.

“My opinion is that investors today are perfectly capable of investing without any state support – all investors need is certainty of time and certainty of regulation,” he explains.

The so-called FER [fonti energetiche rinnovabili, renewable energy sources] decree comprises a number of support tools to boost the renewables market, the most impactful being a series of seven auctions set to award roughly 4.8GW of mixed renewable capacity until 2021.

La Loggia argues that, in relation with the new renewable capacity Italy needs to reach its 2030 renewable energy targets, the auctioned capacity will represent just an uninfluential portion of what is needed.

At the beginning of January [2019] the Italian government published a new plan for climate and energy policy outlining its 2030 targets. Specifically, it pledged to have roughly 50GW of solar capacity – up from a total of almost 20GW currently installed, and 18.4GW of wind capacity – 10 times the operational wind capacity at the end of 2017.

La Loggia notes that the competitive nature of auctions together with the very small capacity available will push investors to compete with ultimately unsustainable bids to get contracts.

“I think the way the decree is structured today needs rethinking. The sector needs a business oriented government that understand what is required and what, instead, could be detrimental,” La Loggia says, suggesting that the government ideally would come up with a scheme where projects would operate on a merchant basis, and the government would provide support on a CfD basis in events of sudden changes in the market.

For example, during Spain’s auctions in July [2017] the government tendered 3.9GW of solar PV and 1.1GW of wind, despite originally planning to award a total of 3GW. The country’s ministry of energy came up with a ‘variable floor’ or minimum pay design to award contracts also to projects willing to operate on a merchant basis, but at the same time offering them a minimum security net.

He concludes, “In that case, the government will be able to attract a much larger number of investors by giving them a very small bit a certainty— which is what investors need.”